I sat in a conference room for 2+ hours where a panel of healthcare professionals asked me questions on J's development and medical history.

I loved that they loved my intense analysis and all the details I gave him about my child.

I loved that they understood everything I said.

…. Not a parent prowling passing hours waiting until she can collect her child from the treatment center.

Once upon a time as a grad student my default face was a scowl and an older man (who may very well be how old I am now: 40; I've become an older woman) who saw me said "Smile, it can't be that bad!" and I ignored him because in my mind, yes, it WAS that bad and no one was going to convince me otherwise.

Now I consciously press my lips upward to soften hard lines on my face because no matter how bad I want to feel about my life: my only living grandparent died on Monday, my only child has autism — I have grown to love my life and I have grown to love being alive.

I said that I've already dealt with those hard times when J turned 2 and he started at an early intervention program.

knowing you were crying most of the time there,

at least at the beginning,

knowing we needed to separate or you'd never know that you can do well on your own, independently from me.

And now look, Dear: Look how easily you have settled into a new class, look how resilient you have become.

We have come a long way, baby.

Me: Do I have to talk about my feelings at the parent support group tomorrow? Because really, I don't want to talk about my feelings.

Moms: No, no, you do what you're comfortable in the parents support group, some parents cry but it's a place also to ask questions.

2.

UCLA Social Worker: Can we meet with you on Wednesday?

Me: Sure…. {while she obsesses over whether she has to talk about her feelings on Wednesday in the 1 on 1 meeting with the social worker, because, really, she doesn't want to talk about her feelings.}

3.

I need energy to get through each day.

I can't afford to spend that energy talking about my feelings, or how am I supposed to get through each day.

Parent 2: "My child is primarily echolalic/scripts all day long…"

Parent 1 and 2 are both waiting for the day when they can finally have a conversation with their children.

Parent 1 and 2 are both waiting for the day when they can get to know their children as individuals.

One year ago, I was parent 1.

Both are painful, in different ways.

This morning someone emailed me about a PhD career video lecture I made in 2009.

I thought of what I didn't yet know in 2009 the kind of life I will have now in 2012.

I couldn't have imagined in 2009 that I would spend 6 hour days roaming the Semel Neuropsychiatric Hospital, waiting for my kid to complete his day in UCLA's childhood autism program.

I try to remember what thoughts occupied my mind in 2009 and I decide those thoughts are stupid compared to the kind of thoughts that have had to enter my mind the past 6 months.

I decide I can't call back the guy who emailed me because I can't talk about trivial topics like my interest in personal development when my kid has autism.

How can I care about the angst of people who don't know what they want to do with their lives when I don't know how the hell to save my own kid's life?

Voice of Reason calls out to me:

You must take care of you!

Pace yourself!

This is not your fault!"

Plus, Voice of Reason, I can't hear you because every pore of my being is infiltrated by the screams of grief.

I can see how sometimes we parents may wonder if we should ask UCLA to work on "more important things" than… for example, potty training.

After all, shouldn't we parents try to potty train our kids and ask the program to do the "more important things"?

What are the "more important things" though?

One obvious deficit we see in our children is social skills.

During our 2+ hour intake when I was asked by the program director what my long term goal was for my child, I said my ultimate goal for my kid was to be "self-reliant, independent, and a contributor to society."

Our #1 priority in self-reliance at this age? Be potty trained.

Nothing says "dependence" like relying on someone else to change your diapers and wipe your butt.

Nothing excludes a child's access to "typical" peers like not being potty trained. Enrichment programs and camps and events for kids often require the child to be potty trained. In this vein, potty training is a critical precursor to social skills.

I did notice more verbalization that is different from his usual language structure (though I can't recall specifics right now, I am nursing a headache from being sleep-deprived…)

The first week for us has been getting used to the early morning wake times, the commute, the general routine of getting to "UCLA school."

The biggest difference I felt in this first week is more related to me: I felt more peace than I'd felt in a long time.

I think the reason is because the people at UCLA have gained my trust, by listening to me carefully and thoroughly when I spoke about my observations and concerns (and I am not kidding about the reams of data I have to share: the size of a 3-inch binder!), by welcoming my questions and then answering my questions, and by their general demeanor of wanting to help me (and also stating and offering their desire to help.) Even the attending psychiatrist (Dr. Suddath) was considerate enough to entertain my questions on clinical studies and mechanisms of actions of certain therapies; with his packed schedule he never once rushed me or made me feel like he was getting impatient. I found him incredibly insightful and compassionate.

I met other moms who have been welcoming even when they didn't know me; I think because we are all in the same boat.

I didn't have to worry that when I dropped my child off, I didn't have to wonder whether he was going to be left to his own devices and ignored. I trusted that the teachers all knew what they were doing, that they were trained appropriately (and well).

Most of all — I trusted that whatever the clinical team at UCLA did and proposed, because I trust that they will do what is in my child's best interest. They do not have some insidious agenda because their funding comes from the insurance companies (god bless the Healthnet HMO and MHN in our case) and therefore they can tell me what they really believed to be what my child needs. It has been a tremendous relief for me emotionally and spiritually and this translates to relief physically even though I'm very tired — when I can trust that the people I leave my Beloved with, are going to do their utmost to help him.

The way I described the way I feel before my experience with UCLA ECPHP is like an animal that has trusted people but was severely injured and punished. That animal was trained that she should not let down her guard because she had done it twice before and paid dearly for it. This time she can believe that she can let down her guard and that these people mean what they say and say what they mean — there are no mind games and twisted rules stacked against her. This time she can believe that she can take a breath for herself this time she can believe that it is OK to exhale, that her child is in the right place for where he is, that her child will be safe.

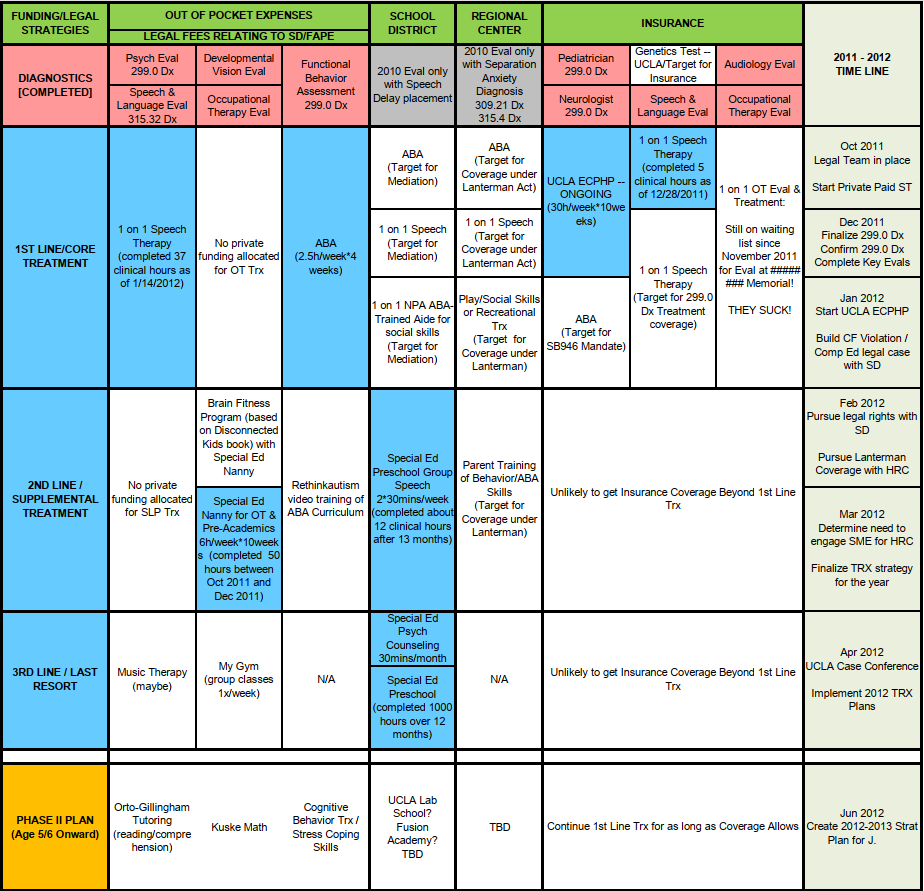

The regional center stalls. The regional center misdiagnoses. Many parents have decided to give up, or move to a different region, or find other funding sources (school district, insurance, private-pay) for getting services for their kids.

We thought about this very carefully. We've already been subject to the status quo (the stalling and misdiagnosing.) It seems stupid for us to bother with the regional center knowing what angst and frustration we'll face.

But it is exactly because of this, that we need to follow through with the regional center.

If all parents give up, we collectively have reinforced the regional center's bad behavior:

Parents are giving up in droves because we have worn them down.

Let's do more of the same!"

This is a matter of other people's kids, not just our own. This is a matter of principle.

Me to other parent in the lounge: I'm sorry, I hope I'm not disturbing you or talking too loud.

Dad: No, no it's ok!

Little Girl: {stealthily approaches me with pages ripped out of a coloring book.}

Me: Hey! I see you colored her hair blue… I like how you colored her outfit red…

Little Girl: {stealthily leaves pages on the table near me and tiptoes away}

Me: This is for me? Thank you! Wait, as an artist, you have to sign your work!

Little Girl: {stealthily creeps back with a purple crayon and signs her name.}

Me: I *love* your name!!!!!!! (It's the name of a flower)

Little Girl: {smiles and goes to hug her dad.}

Listening to parents with two (or more children), I wondered.

If we had a second child who was "typical", if we had this child quickly enough after giving birth to our first child, could I have realized sooner that my first child needed help?

Could I have done something — the right things — earlier, instead of now, when my child is already four years old?

[Side Note: If you have a "typical" child you get to say things like "he is only four," but if you have a child with autism you will be the parents who say "he is already four." That is the kind of different reality -- the kind of time line -- we autism parents live in. I'm still not used to it.]

But I stopped wondering.

We are parents.

We are not pediatricians or psychologists who see hundreds of kids a year.

We are supposed to rely on these experts to know what we don't know and to tell us when something is wrong.

All of us acted when our gut said something's wrong.

That is really the best that we can do, that we are humanly expected to do."

I guess what I was trying to say was…

We don't have to beat ourselves up for not catching our children's autism soon enough.

We can't blame ourselves for not knowing what we didn't know.

We can — we need to forgive ourselves.

The dad tells me they live too far to drive back and forth. They leave at 6am. When the mom works they can't drive the little girl to her preschool because he needs to drive their little boy to the UCLA ECPHP program.

There are toys and books in the parent lounge. The little girl brought her own toys. But the little girl is bored.

She sits on the sofa watching her dad play Jewel Quest on the courtesy computer.

Then she changes her position, first draping her body around the seat of the sofa, then putting her legs up against the wall, pushing time to pass faster.

I have not met the child that this dad and the little girl are waiting for, or all the children on the seventh floor of this building.

But I have already seen the many faces of sacrifice.

Thank you for taking J to 'UCLA school' every day.

I know it's hard, and a long day.

I really feel that we're doing the best we can as parents,

and are doing a good job.

Sure, we could probably do more, but it'd be at the expense of our sanity.

Remember when we were talking about whether we wanted a kid,

and you said it would be an important part of our human experience?

Boy did we hit the lottery!

Sometimes I wonder what we would be doing if we were still childless…

More of the same, with a trip thrown in here and there, but then what?

Now with J my emotional life is full,

I feel a depth of love I never thought I was capable of,

this is making us work together as partners that I don't believe we had ever done in the past….

This is @#$% hard and @#$% great!!!!

I totally agree -

we're experiencing something that goes to the deepest parts of our emotions and souls,

and tests just about every aspect of who we are.

It's very scary for me to even think about what parents of severely autistic or mentally retard children go through, or even deaf/blind.

I'm like: 'how much can a parent physically/emotionally/mentally take?'.

Then I think: 'as much as it takes, to prevent your child from going through worse'.

I just quantify it like this:

every ounce of stress, pain, worry and effort we go through,

takes away an ounce of suffering and hardship from J

(the more help he gets, the more he'll be able to cope and function).

We can't shield him and protect him from the world when he's out there,

but we can do our utmost to prepare him for it.

I got through the mindfulness meditation during the first 10 minutes of the session.

The facilitator then led us through the kindness meditation.

We were to think of a person we could easily appreciate. We were to wish that person well, wish that person to be happy, wish that person to be safe.

I wished my son well. I wished him to be happy.

When I began to wish him to be safe, I couldn't stop big fat tears dropping out of my eyes. Thank goodness most of the people in the room had their eyes closed. But it didn't matter if people saw me; I knew I couldn't be the only person silently crying.

The facilitator then asked us to think of a stranger we'd seen when we entered the meditation room.

wish that person to be happy,

wish that person to be safe.

The facilitator then asked us to wish ourselves well, wish ourselves to be happy, wish ourselves to be safe.

Now that was hard for me to do.

Not without more big fat drops of tears falling from my eyes.

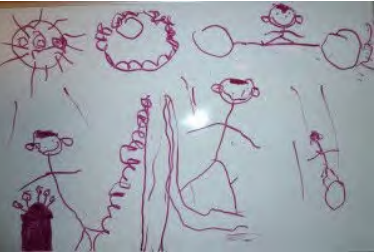

Then he told us what he drew, labeling the squiggly lines with words.

I was so excited, I wrote down those words. Then I drew little arrows pointing those words to the squiggly lines.

This was THE first time our child had drawn concrete objects instead of random circles!

My husband saw my notes and was horrified.

"Why would you write on that? This was his very first real drawing! It's like writing notes on the Mona Lisa!"

I didn't realize what I'd done, because I was so focused on the data of what I was seeing: evidence that our child was already making progress in the UCLA program, a major leap in his graphical communication because he drew a concrete object….

Sometimes I forget to take off the scientist hat and be "mom" and simply celebrate.

To be honest, I was excited to hear this. I too, was looking forward to my 'shiny new different' child.

By the end of the second week, I had mixed feelings because I didn't see a dramatic difference, at least not at the degree I was led to believe by the parents who made those statements.

I wasn't expecting a huge change the first week, since assessments were conducted and this was an acclimation phase where not too many demands were placed on the child during this period. I wasn't expecting much change by the end of the second week, either, since they would still be figuring out the optimal approach to teach while continuing to observe and informally assess.

What I did notice, though, was some new language, albeit not original language and not quite generalized. For example, our son began to ask (appropriately), "Do you hear that?" and put his hand to his ear to gesture.

At first I would confirm what I heard. Then I began to turn the tables to ask him, "what do you hear?" and when he responds (appropriately, although only the word of the source of noise such as a drill or a hammer — they are constructing a new building next to the hospital at UCLA) he responds correctly. However, he does not respond in a full statement with the subject, for example, "I hear a drill." now, if he were to answer this way then I would increase my perception of 'dramatic change.'

The second week was also when I met with the program coordinator to discuss our son's assessment results. This was the most exciting to me, because I would be learning something new about our child's abilities or confirming our speculation of how far he has come.

Prior to his admission to UCLA, we had given him three to four speech sessions a week totaling about 42 clinical hours of one on one speech therapy. We helped him get from almost non-verbal to speaking few word phrases in four months' time. Of course this was also an extremely rude awakening of how inappropriate his placement was at the special day class he had been getting through the public school.

I was under the impression that our child at moved from about a 24-month level of speech to over 36-month level through the intensive speech therapy we had paid out of pocket the prior months. I even thought he may have reached 40-month level or above. However, this was not the case. He tested at around 33- or 34-month level… Not even at three years old for receptive and expressive language.

I was disappointed but upon quick reflection, I had to concur with the UCLA results. The truth is that speech therapists sometimes cue and prompt enough to make a child look more advanced than they may actually be. I don't think the therapists do this to deceive, it may be how they were trained.

Scores don't matter to me as much as true mastery of skill and generalization of skill. The assessment results told us that our child has come a long way from even six months ago, but he has a lot of work to do. I'm so proud of what he has already achieved.

One parent said that in a grocery store, a woman watched her child then asked, "What's wrong with your daughter?"

This parent reacted with a response, "What's wrong with your filter?"

Another parent said that on a playground, an older boy said to her son, "You're crazy!" when her son went up to say hello.

This parent reacted with a response, "You're a brat!"

One parent said that we are more sensitive than parents of typical children; if we had typically-developing kids we may not feel as judged or take these comments as harsh judgments against us personally.

I can't control the environment or other people, their biases and beliefs and filters (and lack thereof) — but I can always control my response to these. I want to learn to move consciously this way, responding to less-than-compassionate people from a place that is compassionate.

I do this more for my own sake than for theirs: I do this to be selfish!

I know there are some people who don't mean to mean, just as there are some who get off being mean, and some people are simply ignorant.

So whatever my response, I'd like to do knowing my son is probably watching me and learning from me — but more than this — there is in every interaction an opportunity to increase awareness of the other person so that they can perhaps be more understanding or compassionate or aware when they encounter the next person/parent or next child.

This all sounds so "great" but I know it is very hard to do, at least for me. I tend to have an emotional knee jerk reaction, and sometimes I over-react.

But I'd like to make an effort and try.

For my son's sake.

For example, I was at the DMV recently, getting a handicap placard for J (this allows me to park in closer spots at the UCLA medical campus) and the lady behind the counter looked at J and asked me 'what's wrong with him?' even though she should be able to read the reason in the application. I didn't feel she meant malice by it, she was genuinely curious.

So I explained. She said she thinks one of her nieces has some issues, although it didn't sound like autism or Aspergers to me. But it did open the door for a conversation and maybe she gained some understanding of the diversity of what autism 'looks' like.

Then the next time when she sees another child, like J, she may have a very different conversation with that parent, with understanding that she gained from our conversation.

Brenda at Mama Be Good shared a different perspective, which my spouse and I enjoyed very much, at Two Sides of the Story. It did make me wonder if maybe some of the people we judge are the very people who share more with our children than we realize.

I talked about the myriad of emotions within the grieving process when I learned about my child's autism. I have resented the lamentations from parents of neurotypical children about why their kids can't start Kindergarten at 4. I have internally rolled my eyes at their stress about what summer camps to send their kids to. I have had to pull the corners of my mouth upward in a phony smile and nod my head as part of my behaving in a socially acceptable manner — my socially acceptable role as a fellow parent.

But deep down I was feeling this:

"Shut up about your trivial problems about your normal kids, you don't know what I'm dealing with on a daily basis!"

I have to go through these emotions because if I avoid these emotions, they will come and get me (I speak from past experience!)

In experiencing these emotions without verbalizing the messages these emotions speak, I also come to realize that underneath the different words we speak, we parents share a common concern: we want our kids to be all right, to be happy, to be safe. Our camaraderie shares the same vein even when our paths diverge.

I tell the social worker:

A parent asked the child what he did today. He said he played. Then he said he got hurt.

The parent immediately knelt down to his level and asked how he got hurt. The child said he got hurt because he fell when playing ring around the posie.

The parent fired questions in rapid succession:

"Do you mean ring around the posie?

Or do you mean ring around the rosie?

Which one?

Ring around the posie or ring around the rosie?"

The child corrected himself: "Ring around the rosie."

The parent confirmed the answer, ring around the rosie.

The child lifted his finger up to his hair.

The parent said, "Don't twirl your hair. Do something else with your fingers other than twirling your hair."

I was standing near the parent and I felt my anxiety level rise. I recognized that tone of voice, that sense of urgency. Only recently, I found myself scrutinizing, critiquing, and testing my own child. I must have caused him anxiety by projecting the anxiety that seethed from my every pore, the way I palpated this parent's anxiety against my skin.

In that moment I caught a glimpse of how my child must feel every day, knowing he is constantly assessed, observed, corrected, tested, and scrutinized.

It's a wonder he isn't more anxious than he already is.

I made sure I walked as slowly as I needed to walk so J would not feel rushed. I bit my tongue on the drive home from testing him with "Wh" questions. I made sure my voice didn't match too closely the tone of his teachers and therapists.

I am not my son's therapist: I am his mom. I want to remember to remain a person my child can feel completely safe with and free from judgment.

This week, I clocked in 2.5 hours of observation.

I realized this: I need to cut back my observation to the minimum 1 hour.

Even if I'm there 6 hours a day waiting, I need to be doing something else with my time. Right now I am still feeling overwhelmed and I've been home almost 2 hours. This week I feel like I've had it up to here (gestures hand above my head) with anxiety.

J's teachers tell me he's doing "really well!"

I include the exclamation mark to convey their enthusiasm.

This is UCLA; they don't say things they don't mean. This is the place where I trust them to tell me the truth about my son's progress.

Earlier this morning, I observed the same session that his teacher felt went "really well!"

This enthusiasm should have infected me with feelings of encouragement and transmuted these feelings into hope. I've read parental accounts of their UCLA ECPHP journey and some of these parents sounded exhilarated. Exhilarated!

But I didn't share the same enthusiasm.

My perspective has been tainted by impatience and parental desperation.

In this brief moment, I can't see the long way we have come. In this brief moment, I can only see the long way we still have to go…. and this is a long and daunting way.

I need to be doing something else with my time.

Or stress will overtake me.

I asked him how he could "keep on keeping on."

He said he had to let go of certain ideas of ambition and career he had for himself, because those were stressing him out.

He said he had to learn to ask himself, "What's my next 'best decision'?" This dad can't even project to the next few hours of his future: he has to live moment by moment.

He said he had to see taking a break as "work" and an essential part, at that.

It is akin to "putting on your own oxygen mask first."

I guess I need to put on my own oxygen mask first.

I observed the teachers working with these children. I felt at once exhausted and awed as I watched the teachers work.

I felt exhausted because I imagined the sheer amount of energy — the sheer amount of will — I must summon, day after day if I were to be working at this level.

I saw how some children preferred to be left alone (after all, there is a reason for the origin of the word "auti" in "autism.") They did not want to be pulled out of their silent place.

I felt awed by these teachers' tireless enthusiasm — their clear and commanding voices — coaxing these children to emerge, for six hours a day, five days a week.

I saw how every teaching moment was a negotiation, paved this way:

Hear my "Uh oh!" and know that an undesired behavior has consequences.

Impatience comes from knowing how much work my child has to do to get to where he can be. But I know my impatience comes from my expectations.

My husband tells me, "If your expectations are causing you stress, then you need to evaluate your expectations."

Fear tells me, "What if he doesn't make enough progress? What if he 'picks up' a new stim? What if he hits a plateau? What if he 'gets worse'?"

What if… what if… what if!

I decide that I was going to focus on the compliment that one of our son's teachers gave us this week.

She said to me, "You've taught him a lot."

She was referring to the self-help skills they had worked on during the day. Incidentally, I was observing the class that day. They worked on basic self-help skills: spitting out water from a cup (for brushing teeth), washing face then wiping face, taking off clothes and putting on clothes.

Through the one-sided mirrors of the observation room, I watched my child follow through each task.

I remembered how we taught him each of those skills.

I remembered how he cried, angry that I suddenly refused to dress him when I had been dressing him all his life. We were in the walk-in closet and I sat on the floor next to him while he tantrumed. I pulled the sleeve that he wanted to thread his arm through, and that was the extent of my assistance. I told my son that he was going to have to dress himself because he could do it. He began to cry. When crying didn't work, he used what he knew I wanted most: his voice. He said, "Help! Help please!"

I remembered wanting to cry too, I was scared that I may be hurting him by being too hard on him. I wanted his voice, but even more than his voice, I wanted him to cultivate self-reliance. I forced my face to appear nonchalant and I steeled my heart against my chest. I kept my voice an even tone as I said that he was going to dress himself that day. He was three and a half years old.

Now I get to take these skills for granted. Because my child has worked hard to earn each and every one of them.

Maybe I'm the one who needs negotiation.

I imagine my child telling me:

Hold high your expectations but know that living on fear has consequences.

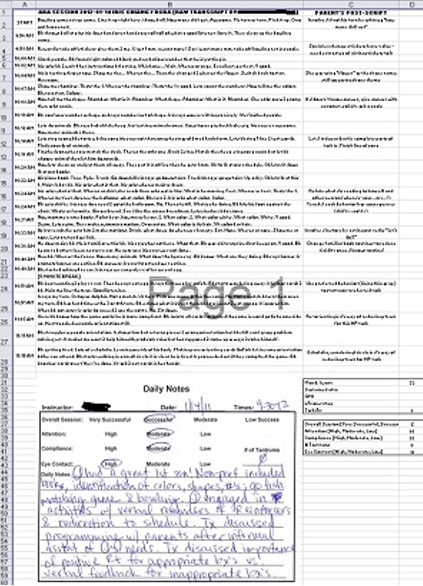

For the ABA sessions, I then transfer the transcripts, plus scanned images of the therapist’s handwritten notes — into a spreadsheet. I then create a data table of the therapist’s data points and generate graphs for each "program."

[Just to give you a glimpse of the severity of my situation and why my husband has to put a stop to my madness!]

To tell you the truth, I do it partly to learn and partly to feel like "I'm doing something to help my kid." It’s only recently that I stopped sitting in and transcribing ABA sessions. Anyway. When I observed my son in the OT session I took no notes. I watched. Then after I was done, I wrote down three key points to share with my husband.

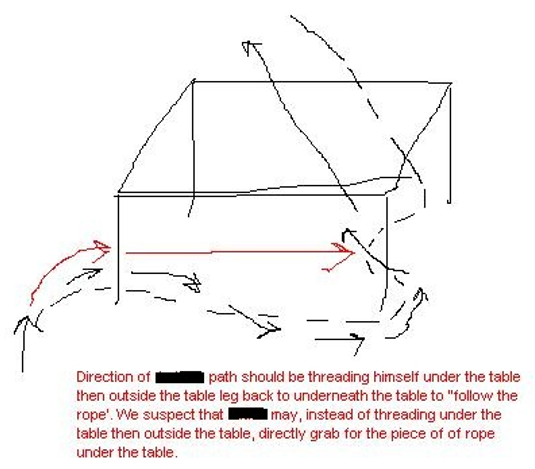

OK, I did make a diagram too, drawing with the mouse in Microsoft Paint. A picture speaks a thousand words, yes?

The OT did this experiment the next day in class and J was able to follow the rope as directed. So not a motor planning issue? More of an impulsivity issue? The mystery continues.

The elevator was very narrow and seemed to fit only the two of us. We were traveling downward at a great speed, almost like a free fall but much more controlled.

I’d forgotten to press the button.

Why wasn’t he talking yet?

Why didn’t he understand our questions?

Why didn’t he understand any questions?

Was it the nausea meds I took during pregnancy?

Was it the Benadryl I took during pregnancy and it “slowed” him down?

(etc. etc.)

In 2011, when J’s behavior grew too strange to ignore, I took him back to his original pediatrician. I knew in my heart that our original pediatrician had been right all along. Only I, like many people, had a narrow and “stereotypical” view of what autism looked like — and it sure didn’t look like my kid! I was ignorant. [We subsequently got a confirmation of diagnosis from a psychologist via a comprehensive evaluation, as well as from a neurologist. I know there are some psychologists who do not think highly of pediatricians diagnosing autism.]

Our diagnosis was almost 6 months ago but I feel like I’ve been living with autism all my life. We go back to J’s early development and now we say, “but of course!” But back then, we did not know what we were looking at, and I still forget not to blame myself for “missing” his autism for so long.

Now the regional center wants their “vendor psychologist” to assess J. Even when we’ve given them about 50 pages of evaluation reports from 2 psychologists who did independent evaluations of J. I’m charged with having to convince the school district and the regional center: “Look, my kid has autism! Do you honestly believe I’m making this up for the fun of it? What’s wrong with you people!”

During some moments this week, I began to feel like a tortured P.O.W., like Jean Luc Picard when he was captured by the Cardassians. I began to imagine that I was “seeing 5 lights.” The medical director saw me struggling and reminded me that my child has autism. I thanked her and tears fell out of my eyes.

“Why won’t they believe me?” I said.

She assured me that this was all about funding cuts and that it wasn’t personal but it didn’t hurt me less. Finding out that my child has autism is a fresh wound that still hurts. As long as the school district and regional center play this game, they forcing open my wound as a parent again and again.

I know people say that the divorce rate in special needs families is high. Fortunately for us, finding out about our child’s autism has made us work together in ways we’ve never worked together before. Still, when I’m stressed, my “safe person” suffers. He bears the brunt of my anger and frustration. But he never complains and he gets up at the crack of dawn to a full-time job every day and when he’s home he will play with J to give me a break.

Sometimes I forget my husband’s emotional toll when I’m too busy trying to shed my own pain and exhaustion from spending 30 hours a week waiting in a hospital. So tonight he told me that everything I feel, he feels too. Right now, he doesn’t have a “safe person.” He wants me to be his safe person (after I angrily tell him, “I should be your safe person!”) but he can tell I’ve hit my limit of what I can handle and he cannot burden me with his sadness and grief.

This whole past week the classes have been "going into the community." Itinerary included a cookie store, the grocery store, and the botanical gardens. The purpose is to generalize what the children have learned and to learn appropriate behaviors in public. I used to equate mastery with generalization but I've learned that "mastering" and "generalizing" a skill are not synonymous.

For example, a child may have "mastered" toileting. The child can complete the toileting routine by knowing the purpose of using the toilet, voiding in the toilet, and cleaning up after self afterward. However, if this child can only "go" to a specific toilet, or with a certain person/teacher, but not "go" potty on a toilet in a different room or different building, or will only go if the same teacher helps — then this skill is not "generalized."

UCLA ECPHP program uses community outing opportunities to generalize skills that the children have mastered, to check that the children weren't memorizing by rote. For example, this week our child was being taught the concept of "not" and "first / last", and when he was outdoors the teachers checked that he could answer probes testing those skills when the environments have changed.

My spouse and I are analytical people, so we also "probe" for mastery in skills at home, which is yet another environment, and this change in environment is a built in "generalization" probe. I was surprised to hear that our son has mastered the "not" concept within a week. Honestly, I was skeptical because I think "not" is an abstract concept. My spouse and I then conducted this at-home test for mastery and generalization of our son understanding "not."

We used a 45 piece puzzle of the United States which he has already mastered. My spouse then asked our son to:

- pick the state that is a certain color

- pick a state that is not a certain color

- pick a state that has a certain picture on it

- pick a state that does not have a certain picture on it

- pick a state that begins with a certain letter

- pick a state that does not begin with a certain letter

To my surprise, our son answered these with 100% accuracy across about 40 trials based on the total number of pieces. What I like about the UCLA "difference" is that they are always thinking about generalization. Good ABA therapists also think of generalization as well as mastery — the key word being "good." I like that I can take for granted that the program my child is in already pays attention to critical details so I don't constantly have to.

We're ending Week 4 at UCLA ECPHP and I'm having to make a decision between the amount of details to share, and whether I'd be overloading readers with information. I know different parents may focus on different things at different times, and I never know whom I may help by sharing a particular piece of information. Thus I'm going to give you a summary of sections to this post and you can pick what you'd be interested in, if you don't feel like reading this very long post.

Summary of Sections:

- [1] Most Significant Change To Date

- [2] List of Visible Progress

- [3] My Own Lessons Learned

[1] Most Significant Change To Date

Here is what to us is the most significant change at the end of week 4: Our child initiated going to potty in the morning!

Way back at the beginning I wrote about why my spouse and I both believe that the #1 priority for our child is potty training, because this is a prerequisite for our child's access to typical children.

By the second week, UCLA started potty training. Our child began holding pee until the diaper went back on. They gave him a juice box or a cup of water every 10-20 minutes and took him to the bathroom on a schedule. Our child also had a potty training partner, another little boy about the same age in class, who had no trouble peeing when taken to the potty. Our child watched as his classmate get M&Ms after peeing. Eventually, when our child stopped "holding out" and peed, the teachers made a big enthusiastic fuss and rewarded him with M&Ms.

By the third week, UCLA reported that our child was initiating going to pee and he had no accidents. This wasn't happening at home since he was still relying on diapers. The few times when he initiated, he insisted on going to a particular bathroom and he'd had an accident en route (he didn't make it in time) or he'd already gone in his diaper by the time he sat down. The teachers told us not to do anything different until they instruct us, but if he initiated, to follow his lead.

By the end of the fourth week, on Saturday and Sunday mornings, he woke up and said "pee pee" and "go potty." He still went to a specific bathroom (i.e. not the closest one!) but he did pee. My husband and I were ecstatic! At least he is starting to initiate going to the potty at home, in the morning.

[2] List of Visible Progress

Here is a list of visible progress I've observed in our child at the end of the fourth week (by the way, each child has his or her individual program, depending on their level of functioning and need, which means this list will have very little meaning to another set of parents):

- Saying "Yes" (instead of almost always saying "No")

- Mastered / Generalized "Not" (we confirmed this mastery/generalization with a home-based experiment)

- Mastering / Generalizing "First / Last"

- Starting to learn "Different"

- Starting to learn "Lion's Voice" (when he starts to whisper or use soft voices when anxious)

- Starting to learn "Strong Body" (when he starts hiding behind adults when anxious)

One behavior he's picked up is saying "no!" loudly, like a defiant little kid would, when he doesn't want to do something. In the past he would shake his head and start to cry or keep saying no. When he did this the first time, at the dining room table when I asked him to continue eating dinner, I was taken aback. I stared him down and gave him a stern warning. But I'm not sure how to feel about this: first of all it isn't as if it was happening all the time to become a problem; secondly this seems so.... "normal" for a little kid to do.

I worry about him picking up maladaptive behaviors because he tends to imitate indiscriminately (our psychologist called this "echopraxia") as well as displaying a high degree of echolalia. During a class observation I saw him imitate a particular behavior (incessant clapping) and one of the supervised volunteers working with him immediately redirected the behavior by asking him to give her a "high five."

I want him to learn stress/anxiety management skills because stress and anxiety precipitate his scripting and echopraxia. I know that if we extinguished one behavior but don't tackle the roots of stress and anxiety or give him tools to manage these feelings, new behaviors will simply emerge to displace old behaviors. Stress/anxiety management skills will be a key focus area for our child now and as he grows.

[3] My Own Lessons Learned

Even though this past week has been somewhat of a "hell on earth" because of what the regional center is putting us through, I've had memorable moments. This past week I was talking with this dad about accepting our children's special needs. He recalled a mother who was crying hysterically because she saw her child's diagnosis as the end of all the dreams she'd ever had for her child.

I loved this!

Not 6 months ago, when we learned that our child was not "just a late talker" but has autism, I began grieving for what I thought I could take for granted with my child. I thought I would be worrying about which universities he would attend — I never imagined I'd have to worry about whether he could even make it through the educational system to enter university. I, like all parents, want my child to be safe. Overnight, keeping my child safe took on whole new meaning across a whole different timeline. My morbid question used to be, "what if I die and my kid's still young?" and post-diagnosis my morbid question has become, "what if I can never die because who will make sure my kid's OK?" We have an only child.

I grieve every day. There is no clean time line for grieving — no neat process for the stages of grieving (no matter what I've read, it doesn't happen neatly or cleanly in that particular order! I recommend Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking for a more accurate reflection of the grieving process.) Still, I try to make sense of what I'm going through by giving value and purpose to my experience. This does not lessen the pain, but it makes the pain more bearable. I'm not quite sure how to create new dreams for my child... not yet. The upside is that I did not have a lot of emotional baggage from old dreams, because I'd started out with a very open mind when I became a parent. Yet I feel disoriented, not sure how far into the future I'm supposed to learn to expect and project, when now I'm told to take things one day at a time, to live day by day.

I'm not a person who take things one day at a time. I'm the person who chunk time in quarterly periods, evaluating my accomplishments, then projecting where I'd like to be the next quarter or year. My not living "one day at a time" gives me a lot of pain (past) and fear (future) with our child's autism diagnosis. I'm either reliving the past, "why didn't I see it sooner?" Or I'm fearing the future and what challenges my child may face.

I now understand that part of my resisting "living day by day" is that my mind assumes I'd be giving up my strengths of planning the future — skills that have served me well in career and business.

My organizational skills and projecting prowess have helped me create a plan of action for our child as soon as he received the diagnosis. I need to assign my strengths where they are needed, and focus my attention "today" for self-preservation.

You know how sometimes you as a parent get caught up in the wave of what's trendy, what you should be doing for your kids with your kids? Well, take that, and multiply it by 1,000 and then punch in a million units of heartbreak if you're a parent of a child with autism. There are too many "treatment" options, too many anecdotes and "N of 1" testimonials, too many things to spend money on regardless of whether you actually have that money to spend. [I put "treatment" in quotes because most of the time there is no scientific or research-based evidence backing claims of effectiveness.]

Before our son started with UCLA ECPHP, I spoke on the phone with Elizabeth Harrington (contributor to Rebecca's Story in Behavioral Intervention for Young Children with Autism.) She said something I'll never forget, especially now.

I paraphrase:

Sometimes I feel like I'm bombarded with statements of my peers who are trying literally everything they can afford, to the point where my scientific brain and common sense get worn down and I start wondering why I wasn't doing more, whether I should be doing more. It's not only about financial loss, that I loathe with the selling of most so-called "therapies", even as that money is significant: parents have spent thousands and thousands of dollars on "treatments."

If I put on my "the world is not black-or-white" hat, I can say that there are some of these salesmen that honestly believe in the products they sell. Some of these people are even medical doctors and psychiatrists, very intelligent and highly educated people. Not all of them are "in it for the business" although let's face it, autism has become a lucrative industry. Still. When the shards of broken dreams pierce parents' already broken hearts, the salesmen move too easily onto their next customers, targeting the next sets of hearts clinging onto any hope the parents can find.

It's about breaking someone's broken heart, over and over again.

Actually, I called this day, "UCLA day #whothehellcares"

Before.

Taking care of myself today means skipping the mandatory "parents support group" and hiding in the adjacent conference room to cry by myself. Staring into space. Wondering about the lives of the people whose portraits are on the wall of this room. Trying to pull myself together enough to step out of the room without tearing up. Wondering where area code 760 is and why I'm getting a call from there. Not picking up the phone because I can't open my mouth to stop tears falling out with the words I'd have to say like "hello." Wondering when Janice will come in to ask me to leave. Tearing up because Janice is kind and letting me hide in this room. Blaming the tears on PMS, the weather, fatigue, school district refusing to believe my little boy has autism and forcing us to use a legal hand. Crying because I didn't feel competent being even a regular parent how the hell will I know what to do being a special need parent. Telling myself to cry more quietly because people can hear. Looking at the clock and calculating the number of minutes I have to pull myself together again for the next support group that I don't want to miss. Saying to the mom who peeked in, "yes, come in and breast feed I don't mind as long as you don't mind my sobbing." Telling myself now I really need to pull myself together. Trying to think of something funny so I get to "not crying" faster. Shit. This sucks.

Later.

Oh. My. God. I look so awful. I stepped out of the room to use the bathroom and I look a mess. I know this sounds so superficial but I wish I can cry pretty, tears falling out while my face keeps glowing. Like they look on TV. Oh yea that's called eye drops and makeup.....

Later Still.

I realized just now that if I told people I have a heavy cold, my puffy eyes and snotty nose will not cause concern for my emotional state and people will stay far away from me and not try to console me.

Even Later.

I'm told that this is all part of the normal grieving process. That I sometimes need to leave the premises and go for a walk.

Are you going to the free drop-in meditation on Mondays? Yes, I went yesterday.

You're feeling very raw right now. You have to process it, you can't rush the grieving process.

I wish I can just TIVO this part and get to the program!

Yea I really said TIVO. We don't even own one (we rarely watch TV) but I sure wish I have a Life-TIVO and skip all the "being screwed in the mind by school district and regional center" crap and cut straight to happy ending*.

I want to thank a mom who reminded me today that our kids aren't perfect and that none of us are perfect, and to not be so on edge and hard on myself about not being perfect.

It took guts for her to say it and I know she said it in my best interest.

On Thursdays I meet with the staff psychologist to discuss J's progress and goals. Today my husband accompanied me, so he can hear the updates and observe a class and ask questions. We're half-way through the program and we realized that our child is very complex: he demonstrates significant strength in some areas, and significant weakness in others (like speech.)

We're half-way through the program and the psychologist isn't yet certain how to answer our question about our child's learning style: because she sees the complexity of this child and the different layers they are peeling back as they learn about him weekly.

My spouse said that at first he wasn't sure what to expect from the program... certainly the therapeutic/teaching component is a critical part of our figuring out how to help our child succeed. But as our child continues with the program, as I observe and share insights I have with my husband, and I discuss J's progress in weekly updates with the psychologist...

Yes, we do want him to receive "teaching" and "therapy" as part of his behavior treatment for autism, even as we don't believe in "fixing / curing" his autism (just as I don't believe in "fixing / curing" my depression, although this hasn't prevented me from having an incredible quality of life.) But the most important service UCLA ECPHP can provide to us parents is the multidisciplinary pairs of eyes learning about our child, observing how he learns and what he is motivated by, and helping us parents give him the tools and skills he will need to blossom and realize his full potential.

Because we can see in this child — he is full of light. We want to understand all the different ways he shines.

1.

Sometimes it's not just about the progress I see in my kid that makes my day, I mean — REALLY makes my day. Sometimes it's the change I see in another child. Like getting a hug and even a kiss from that child! Like seeing that child smile and run up to his mama! I see the change in this child and how different he appears even to my untrained eyes. This makes me feel really happy.

2.

This is something I kept putting off from writing... because I was afraid I'd start bawling if I wrote it, and I don't want to be bawling on Floor B near the fish tank where people are coming to and fro! (Then how would I maintain my "superwoman" facade?) But I wrote it nonetheless (and it did make me cry, and thankfully no one was around at the time.)

Dear J –

I promise I will look first at your strengths before I look for your weaknesses.

I promise I will see the fear behind your anger and tantrums, and respond to that fear instead of interpreting it as you being spoiled.

I promise I will be your mama first and foremost and above all other roles.

I promise I will lighten my step, lighten my brow, and lighten my hand when it comes to teaching you the ways of the world.

I promise I will trust your strengths to carry you through when I can no longer carry you.

I promise I will carry you for as long as I am strong enough or until you stop asking me to.

I promise I will trust in you.

I promise I will trust in me for you.

We've been pleased with our child's progress in speech, even as progress feels slow. As long as progress is steady, I'll make peace with "slow." He is making more comments about his environment, like "no cloud today" when he looks at the sky, or "mommy is coughing" when he hears me in a coughing spasm (I think I've caught whatever Alice Y. had caught last week....)

UCLA is teaching our child joint attention skills, which starts by him pointing and asking "What's that?" or "What is that?" I can testify that our child is picking up this ball and running with it: yesterday when we went to the grocery store he was continually pointing and asking "what's that?" At one point I felt somewhat annoyed by his incessant "what is that?" and then I realized that I was feeling the annoyance of what regular parents would feel when their regular kids started asking "what" and "why" questions, and I was grateful for this glimpse of normalcy.

Our child is doing well in the potty training department: On Friday I forgot to put a diaper on him before bed, and to my surprise (and relief) he stayed dry overnight and then went to the potty to pee after he woke up in the morning. Sometimes he will take himself to the bathroom without announcing to us and requiring us supervise/help, which is awesome. He's certainly mastered peeing in the 3 toilets in our house — next challenge is to generalize this across different environments a.k.a. public toilets. Since he's scared of the loud sounds of public toilets flushing, this will be a challenge. As for doing the #2, I'm not sure how we're going to work on that... it's something UCLA will have to teach us.

This week marked a shift in our thinking as parents on how UCLA ECPHP can work with us as partners in helping our child unlock his potential. As I mentioned, earlier in the week my husband took a day off work to come to the weekly clinical update meeting with Dr. K, the coordinator for the ECPHP program.

I had emailed Dr. K a list of questions I had on our child's educational environment: what is the optimal environment for him to learn? I began to think about this as I listened to other moms talk about post-UCLA placement for their kids, which schools they're looking at. Since we live in different areas, those schools I've heard about are too far for a daily commute and that would negatively impact our child's quality of life as well as ours. I know that good schools having waiting lists. Charter schools run lotteries. Private schools are expensive. Public schools... well, we're dealing with a public school right now and let's just say that lawyers are involved.

My child's education has been on my mind constantly. But how does he learn? We don't quite know yet. My husband and I do what we can to look for any clues we can find when we step back and watch our child access his environment. We look for all the ways this child figures out the world, all the ways this child wants to connect with the world or be part of the world. We are confounded by this child, who randomly reaches for words to verbalize in a simple sentence ("She has sitting" instead of "She is sitting"), but who can look at puzzle pieces flipped upside down and backwards and know exactly which shape he is looking for. This is a child who struggles with verbal language, but who has perfect rhythm and pitch for music. Many people can't understand many of the English words this child says, yet he can enunciate foreign words with the right inflection like a native speaker.

I can only speak for this one child. But I have a feeling that many children on the spectrum are equally mysterious and equally complex. These children access their environment very differently from their "neurotypical" peers, and they may appear very behind or very delayed or even "disabled" in some areas, while demonstrating a high degree of proficiency/competency in other areas that their "neurotypical" peers may struggle with. I think this may be more common in children — neurotypical or on the spectrum — than we realize. We've grown used to the idea of "typical" because we are using statistics to measure what is "expected." This is why children on the spectrum are almost impossible to categorize or for experts to lump together so that a "standard method" may be created to "teach" them or "reach" them. This is why children on the spectrum require individual instruction, tailored to that child.

As part of our quest to better understand our child, I asked a special education consultant/advocate to come to observe our child for a couple of hours. This is a person I trust and respect, who has given me an incredible amount of guidance when it comes to helping my child. I've implemented one of her recommendations (start J on drum lessons with music therapist Michael Dwyer) and J absolutely *loves* the sessions. This 4 year old (who has an "ADHD impression" from a neurologist) stays engaged for a full 50 minutes. When my son's working with Michael, the smile and look of wonder on J's face is more like therapy for me than for him... It's so healing to see my child so happy.

I've been toying with a hypothesis for ways that J can better access language... and I'm not sure if I'm completely off-base, but based on our parental observation of this child's strengths, based on Nan's feedback, based on feedback from the UCLA team that this is a complex child difficult to figure out...

I want to test this hypothesis while we are still taking him to UCLA, so if my hypothesis turns out correct, then our child can experience an increased gain from his time at UCLA. This hypothesis sounds so crazy, it just might work.

I feel like I live a double life.

There's the life of the autism parent, advocating for my child, fighting for the services he needs from the school district and the regional center, staying alert to any clues of his strengths and how he processes the world, keeping on the pulse of ways of instruction that teaches to his strengths, meeting with my child's clinical team, updating my spouse on our son's progress, observing my child in class, trying to keep my head above water while occasionally overcome by a tsunami of emotions and exhaustion that leaves me gasping for air and a second box of tissues to wipe away tears and snot.

Then. There's the life of the adviser mentor consultant, facilitating career transitions, asking brainy PhDs questions of the heart (these are research scientists looking to leave academia but wondering what job prospects await them, if any, beyond the ivory towers), helping a MD go through a clinical presentation he has to give as part of a job interview, sitting at the courtesy computer on Floor B parent lounge and hearing myself analyzing the MD's slide deck saying, "cut out this slide.... Spend only 30 seconds summarizing this slide..." and at once wondering to myself, "which person am I living right now? The autism parent or the adviser mentor consultant?"

I know I'm supposed to say that I am one and the same, embodying all roles that make my life as multifaceted as life is, that I live deeply embedded in the world of autism especially when I spend at least 30 hours a week physically at UCLA ECPHP and yet I fulfill these other roles in these other different worlds.

But I've grown used to compartmentalizing so that I can function and be mostly effective. I am not always successful. I feel like I have lived about a month's worth of time within a given UCLA ECPHP week, and something that happened last week feels like it happened last month. So many events seem to pass during each six hour day even as the day seems to take too long to pass before I can go to the seventh floor to watch the closing circle time and say hello to my child. Maybe this is why I feel old, older than I have felt in a long time (although technically I am indeed getting old because I am 40 this year.)

Crossing over chasms that feel worlds apart can take a lot out of you.

After my skipping the mandatory parent support group last week because I couldn't keep on my "functional face", I attended the group this week. We went through introductory remarks then the facilitator invited us to share whatever we wanted to share. I said that we are now going through the "due process" process with the school district. I mentioned that last week I had a really hard time keeping myself together to come to the group. That I felt completely overwhelmed.

A new parent said that as hard as it can be to not get emotional about our children, I needed to "man up" and get through what I needed to get done for our kids. I said that yes, I had "been there, done that, doing that." I was a master of compartmentalization (New Parent: have you met my spreadsheet? And all the post-it notes that was the spreadsheet's progenitor?) but all the compartments have overflowed.

Being told to "man up" really bothered me. I had been telling myself for months that I needed to "suck it up." I had been telling myself I needed to "man up" and get fighting — there's no time for sobbing and being vulnerable. Then the social workers at UCLA have been trying to convince me that I can give myself permission to grieve, to be sad, to cry. I listen to this parent trying to be helpful and I realize that I had been telling myself to "man up" all these months, thinking it will keep me stronger and functional longer.

I saw crying and being emotional as me becoming a wimp. How could I possibly fight for my kid if I were a wimp? But I needed to shed this past week's tears. These tears were blocking me, man. Keeping them silent and swallowing them down may give me the appearance of "being a strong parent," but the price was hardening my heart and a flaming case of heart burn. Plus, who decided that "being a man" means not crying? I wish more of our dads have open permission to cry, to grieve, to let loose their fears and tears and feelings. Dads feel as deeply as moms do. Dads are human beings. These dads love their kids as fiercely as the moms love their kids, they fight as relentless alongside their partners for the sake of their children. Why aren't dads afforded the same luxury of being vulnerable as moms are?

Being vulnerable is scary.

I choose vulnerability. I choose this class of strength.

And this is how I "man up."

We had to "take off" days 30 and 31 from UCLA because my spouse had an auto accident.

For the past few months, his "classic" car was being repaired. Since this had been his commuting car, he took his back-up mode of transportation: his motorcycle.

His commute is not far: about 4 miles each way. He's a careful motorcyclist. But this doesn't mean other drivers are thinking about motorcyclists on the road; they are used to expecting cars on the road.

I knew that no matter how careful you are, accidents are often a game of chance. The more times you're on the road, the greater the chance you'd be in an accident of some kind.

This was what happened mid-week. My husband had the "right of way", but the other driver didn't "see" him.

To avoid being hit by another driver who wasn't expecting motorcyclists on the road, my husband swerved and both he and his motorbike went down on the road. He suffered cuts and scrapes, bruises and contusions and a fractured rib and fractured ankle.

Thank god.

Thank god he wasn't knocked out (concussion.)

Thank god he was wearing a helmet, his motorcycle leather jacket, and a backpack; these protected his body from worse injuries.

Thank god one of his coworkers happened to drive along and see him and stay with him until the police came to take eye witness accounts.

Thank god this wasn't heavy traffic rush hour where other cars could have run over him when he hit the road.

Thank god our life insurance policies are up to date. If something happens to one of us, the one who's left will have the means to take care of our child.

I handled the news of the accident surprisingly well. I think my bout of crying last week really helped my composure with the events of this week.

The accident was one of the "lows" this week.

(The other "low" would be our filing a due process complaint against the school district with the state's Office of Administrative Hearings.)

We had a restless night as a family, that night.

The next day, our kid did the #2 (pooping) in the potty.

I mentioned before how important potty training is for us as a developmental goal. The UCLA ECPHP team got him to the point of initiating peeing in the potty and our child was generalizing this at home, but we were told that pooping in the potty will be tougher to teach, especially if his regular "#2 schedule" didn't occur during the hours when he is at UCLA.

But the day after my husband was in the accident and we all stayed home to make sure my husband was OK, our kid did the #2 on his own.

My husband and I had been waiting for a year for this developmental milestone.

We were so happy, we hugged each other and cried.

But really.... I just wanted to hug my husband and cry with him.

After a rough week, I'm looking forward to bringing J back to UCLA tomorrow.

J misses his UCLA teachers too; he said "UCLA school" a couple of times this weekend, and said the names of the different teachers. I think he appreciates being taught the way he's taught by the UCLA ECPHP team!

Interacting

J's immediate echolalia has reduced significantly. We still have quite a bit of scripting (delayed echolalia), he still struggles with answering Wh questions, but we have more functional communication and it feels like we are getting to know our child more. My husband feels like he understands more (increase in receptive language.) We're starting to see more of his personality shine through. We have been waiting to get to know our child for a very long time.

Moments of "Normal"

- Like him bargaining with us like a regular kid: "May I have three M&Ms?" No, you may only have one, because you didn't completely finish your dinner. "Two! Two M&M's." Um... OK, two... (so I'm no Tiger Mom.)

- Like him asking "What is that?" incessantly, like a regular kid when a regular kid gets to the "what... why...." stage. I look forward to the "Why" phase but I know it won't be for a while.

- Like him saying "Hello!" and waving to people. Random people, even when they aren't looking at him thus can't know he's greeting them, but I don't care. This kid's an extravert and now he's getting the tools to develop his extravert personality.

Complete Toileting

This one is a big deal. Very big deal.

We've been waiting for a year for this to happen, and we couldn't do it on our own.

Singing

J always liked music and songs, but before he could only follow along with music and sing maybe the last word of each song stanza. Now he is belting out entire songs (he doesn't know most of the words and he makes up whatever sounds he thinks those words are.)

J sings continuously throughout the day: when he's walking, when he's bathing, when he simply feels like singing. Made us realize how he was unable to do this before: he did not have enough language and he didn't have command of the means to use his "voice." Now he does.

He still has a lot of hard work ahead of him in the speech department, but now he gets to do something he loves, like singing at the top of his lungs.

Music to our ears. Literally.

Setback? Not really...

One strange thing my kid did/does is covering things up. He'd use a blanket or a piece of cloth or a jacket or even a hat or a cap to cover up objects. About 6 months ago he was constantly covering up things: he'd cover a cup with a hat, he'd cover a toy car with a blanket, he'd cover the top/back part of a chair with a jacket...

Before the UCLA program, I hired a babysitter who has experience working with special needs children. She'd work with him two hours for three times a week before he goes to the "special day class" (special ed program of public school.) She'd do different physical / sensory activities with him like playing with beans, playdough, paint — and his "covering" things up behavior ceased.

Then when he did cover something up, it was appropriate: he'd cover up his scooter and say that was his motorcycle (my husband rode a motorcycle to work and my son noticed that when the motorcycle wasn't in use, it would be covered up.)

In the past 2 weeks he began to "re-cover" (OK, bad pun.) He'd use a blanket, line up two of his toy trucks, and cover those two toy trucks. There, on the carpet floor, he'd keep them. Covered up. Once they're covered up he doesn't bother them. But if I remove the cover and put the trucks back, the next day he'd go through the same exercise.

I don't let this bother me. I suspect this old behavior is a coping mechanism.

The kid's been bombarded with intensive instruction for the past 6 weeks.

It's stressful.

They're extinguishing his immediate echolalia.

It's a big change.

I see the old covering behavior as a way for him to cope, to feel in control or comforted. I don't subscribe to the belief that I have to eliminate ALL behaviors that look weird. I have no problems letting him have one or a few "quirks" that aren't intrusive.

I can't believe we're more than half way through the UCLA program.

Every day at 1:30pm all the parents can cram into the observation rooms to observe the last 30 minutes of "class."

For my child's class, this is usually the closing circle where the children are asked what they did today, what day this was ("Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday is the Bus Ride Day!") and then the children select cards of songs they want to sing before the day is "wrapped up."

I marvel at the progress of one of my child's classmates: this child is smiling more ("positive affect"), is participating more, and initiating more; to me this child has made a huge leap of progress from when he started.

This child's mother looks at my child and tells me when he started she perceived my child to be reserved and quiet, and now look: my child is singing and smiling and laughing: she tells me she sees the huge leap of progress in my child.

I have a love-hate relationship with the weekly mandatory parent support group.

On the one hand, I want to go, because I can learn snippets here and there of useful information or insight about dealing with the school districts or the regional center or what I may want to look for when I scout behavior agencies once my child's done with UCLA ECPHP.

On the other hand, I don't want to go, because I feel a certain "peer pressure" to do certain things in certain ways or else I may look like I "don't want to do everything I can" for my kid.

So, no, I'm not going to "suck it up" and sell my house to move so I can get a different school district or regional center, even though it seems to be a logical thing to do, because of a myriad of reasons, one of which is "on principle, so as not to positively reinforce unethical school districts and regional centers to perpetuate their war against parents."

And it doesn't mean that I don't want to do everything possible for my kid. I'm the parent who at one point had been thinking 2 or 3 generations ahead. That's right, I am not saving only for my child, but for his children, and his children's children.

Parents and families have different philosophies and timelines and situations.

This doesn't come across readily in a forum where we can only touch on topics superficially.

Like this week I chose not to mention my husband's accident and injury, because I'm focused on the new mom looking overwhelmed and about to cry, and I want to send her invisible waves of support. Meanwhile it does not allow me to explain why I fail to express any enthusiasm for suggestions that I sell my house and move or spend an extra $1000 a month to rent a place in a "better" school district.

The meetings feel like a live Tweet chat stream, opinions are pinging so fast — too fast for me sometimes.

But I also know, whatever bothers me about what I'm seeing or hearing, may be because I'm looking at mirrors that remind me of how I used to be and may still be.

I observed J in an OT (occupational therapy) session today. The therapist hung a purple colored "cocoon swing" / "cuddle swing" from a ceiling hook. She asked J to get into the swing.

Wait –

There's another child in the swing! J gets anxious around peers (children)! He'd be in close physical contact with a peer! (O!!!!M!!!!G!!!!!)

For some reason I thought of this Far Side Cartoon:

But it turned out J did just fine, swinging with another child.

Today, UCLA ECPHP administered the ADI-R (Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised) with us. My husband was still in a lot of pain from the accident and had to remain at home; we teleconferenced him in.

The ADI-R served to complement the ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) that our psychologist had conducted 4 months ago.

I could say that the structured interview was "a success." My husband and I recalled with a high degree of specificity the details of our child's development, what we noticed that were atypical, some of the behaviors our child had shown that we did not understand, our struggles in coping with our child's behaviors and tantrums when he had no language.

I was glad that we will have a robust level of "evidence" to strengthen our case against a school district we believe had denied our child the appropriate public education he's entitled to.

Then.

I was sad because I am reminded, yet again, that my little boy has autism.

Yesterday, a psychologist working with the regional center observed J at the park, as part of the regional center's determination of J's eligibility for services under the Lanterman Act.

At the park, there were kids practicing softball in the batting cage.

My secret wish had come true: one of the adults in the batting cage turned on the softball pitching machine.

I knew that once the ball pitching machine was turned on, J would be fixed on the pitching machine and he wouldn't care about anything else.

The park was full of children playing on the structures, and J behaved as if he couldn't see them (he really couldn't, since his back was turned to the playground and his eyes fixated on the mechanical arm pitching softball.)

The regional center psychologist spent much of the time watching J looming around the pitching machine. Occasionally, J would run around the perimeter of the pitching machine, then resume his fixation on the pitching machine.

The psychologist asked if I could get J to go to the playground, away from the machine. I made a good faith attempt by offering J the option and I was not surprised when he said no.

I could say that the observation was "a success."

For the duration of the observation, J initiated no peer interactions with the playground full of children. He minimally interacted with the psychologist. He showed little to no curiosity of what other kids were doing in the playground. He didn't even look at the kids in the batting cage who were practicing hitting the softball. He was completely attentive to the softball pitching machine.

I was glad that I didn't have to go to extreme measures* to prove that he has autism.

Then.

I was sad because I am reminded, yet again, that my little boy has autism.

*the way I've heard some parents were pushed to do to secure services their children needed, by starving them or keeping them way beyond their bedtime.

Sunshine Boy

What J's teachers call him.

"Hello!"

What J now does (most of the time) when he sees someone, accompanied with a big smile and hand wave.

Cries and Hides

What J used to do all the time when he sees someone, accompanied with death grip of my leg or arm.

Snack Leader

A role each child plays during snack time to learn to listen to their peers' requests for snacks.

Pirates Booty

Something I've never heard of until J's classmates brought these for snacks, and J decided that the phrase sounds hilarious and that he should say it often.

3

The number of bags of Pirates Booty I bought when I thought J really wanted this snack, given how often he says its name.

0

The number of bags J ate of the 3 bags of Pirates Booty I bought (guess who ate all 3 bags.)

5

The total number of bags of Pirates Booty (and I'm talking about big bags, folks, not those wimpy "fun size" bags) I have eaten in the last 3 weeks.

"Must be able to lift and swing at least 35 pounds"

What UCLA ECPHP teachers' job description must say because they pick kids up and swing them around and hang the kids upside down and the kids love them.

Young

How the UCLA teachers look to us when they're swinging J around and hanging him upside down and he's giggling with delight.

Old

How we feel watching the UCLA teachers swinging J around.

(I almost threw out my back just watching them do it.)

Over the weekend we went to a friend's child's birthday party. That child turned two. J was one of the two older children there, the other kids were younger, between ages 1.5 and 4. It was one of the more "mellow" birthday parties. Does it help that the majority of the families came from Hawaii? I love the laid back "Hawaiian" attitude. When we walked up to the house, the dad was inflating balloons. The loud sound of the pump he was using scared J and he wanted to be held. I held him and we went into the house. The little birthday girl was a quiet child, she and J had met before and J is comfortable around her.

As children began arriving, they went to the big inflatable "bouncy house," which had a built in obstacle course (including a basketball net and a slide.) My husband had to coax J out of the house. Once we got J into the bouncy house, he had tremendous fun! He went down the slide, climbed over and under the obstacle course, jumped around and laughed. Like a regular kid would.

Our hosts made a "fishing game" by filling an inflatable plastic pool with water. There were laminated shapes of paper fishes with paper-clips glued on them. The children would take wooden fishing "poles" with magnets attached at the end of the string to "catch" the fish. When J caught a fish, he'd shout, "I got a fish!" He was delighted and had a big smile on his face. Like a regular kid would.

Then we crowded around the birthday girl, and J sang the birthday song and, like the other kids crowding around the cake, wanted to help blow out the candles.

Saw Alice in the hall and asked her about the inevitable:

Discharge Date.

We went to her computer and she looked up the records and.

April 20.

(Hopefully not earlier. Fingers crossed.)

In the afternoon I met with Dr. K for our weekly meeting to discuss J's progress and goals. She said, with concern, that I seemed "low energy" recently. She quickly disclaimed that her comment had nothing to do with how I appeared*.

It's true. Fatigue is filtrating my being, physically and emotionally. Maybe... It's the combination:

Grieving for the recent past (diagnosis) -

Struggling through the present (of which UCLA serves as a respite for my sanity albeit with a stressful commute) -

Worrying about the future (post-UCLA) -

No amount of "sleep" may allow me to evade this exhaustion, although having more better nights' sleep can surely help. I haven't slept decently since... I don't know, most of my adult life (? I suffered from depression, and sleep disruption is usually a marker symptom, then once the medications get on board, some disrupt sleep as a side effect.)

Or Maybe... It's because:

Tomorrow's the last day of one of J's classmates. I've grown used to the companionship of that child's mom. And I wonder who will go with me to "Cafe Med." And how our kids will no longer run on the patch of grass on the rooftop parking lot at the end of their day at UCLA. And how she'd make me laugh by waving her arms, a la Sound of Music's "The Hills are Alive!" It's the little things that make bearable these 30 hour weeks away from my comfortable shell. Like having a friend to go with to Cafe Med. Like feeling safe with her to talk about fears that we both understand as "autism parents." Like appreciating "pirates booty", which she now also likes, but in moderation (unlike me, Ms. "I eat entire bag-fulls.")