This is my in-depth report on Dr. Tanya Paparella's new book, More Than Hope for Young Children on The Autism Spectrum: A Step-By-Step Guide to Everyday Intervention.

I met Dr. Paparella (I call her Dr. Tanya when I was there) when J was at ECPHP. Dr. Paparella is one of the two medical directors supervising ECPHP and oversees the class J was in (Sunbeams) as well as the younger class (Crystals.) The very first day when I was in the 2-hour intake process, a graceful lady walked into the room and extended her hand to me. Dr. Tanya Paparella introduced herself, and I felt at once shy and smitten with her serene presence and her accent.

I would get more time with Dr. Paparella during our child's stay at ECPHP, as I would ask her questions that would mystify or frustrate me. She is incredibly busy, yet she stops in the hallway when she sees me or another parent and offers her smile and quiet support. She never made me feel hurried, or that she was too busy for us. She thinks very carefully my questions and answers to my level, which means she makes the effort to get to know me as a parent and where I'm coming from. She has the difficult job of reminding me that my child has autism when external forces planted seeds of doubt that made me question my sanity. And she did all of this with a level of compassion and love that we parents can feel throughout our journey with our child at ECPHP.

I write the above preamble because I want readers to understand what they can expect from this book, and why I was not surprised to see that Chapter 1 was Courage, and why I smiled when page 2 offered a bolded statement: "parents do not cause their children's autism" that was followed up by "young children on the autism spectrum can make enormous change and achieve what seemed impossible." I have heard Dr. Paparella say this to us parents during her weekly support group and heard her explain what we can do to help our children and still remain our children's parents. This is a book that believes in your child, because Dr. Paparella believes in your child and more importantly this is a book that is compassionate toward you as a parent, and holds you in positive regard as a parent.

Chapters 1 and 2 are fundamental chapters to dealing with the emotional aspects of finding that you have a child on the spectrum. Besides courage (whether you believe you have it or not, you will draw upon strength you didn't even know you had), chapter 2 discusses signs and stereotypes that newly-diagnosed or peri-diagnosed (I made this term up to mean: you're not officially diagnosed but you strongly suspect and probably made that decision within your heart even as you're yearning to hear a professional tell you that you're wrong) parents hold, such as autistic children aren't affectionate, they don't speak, they always don't have eye contact, etc.... the stereotypes that confuse and cause delays in children who need to receive the diagnosis so that they can receive the appropriate intervention. Don't skip these chapters even when you are eager to get to the chapter on language.

Chapter 3 speaks to a focal point of many parents whose children are on the spectrum: Language. Language deficit is probably the most visible warning signs that "something is amiss" for those children who don't fit the stereotype of "what autism looks like." I like how Dr. Paparella helps parents "see" from their children's perspective, guiding parents to follow the child's lead first and aim for contingent language teaching ("Join your child's attention.") Next, scale your language to your child's level. This makes a lot of sense but we adults have become so used to complex language with undertones and overtones that we need to be reminded to keep it simple. Imagine yourself learning a foreign language. You'd want to hear distinct words, preferably one syllable words that correspond with a concrete object (nouns) or action (verbs) first. Otherwise you'd be confused. Imagine how much harder this is for a child who hears every single sound in his environment and has to learn language from adults' fast and complicated utterances. These sounds become a blur to the child. What I like about Chapter 3 is how the method is direct and clear and actionable.

Chapter 4 builds on Chapter 3 and discusses an aspect of language that many parents of kids on the spectrum may not readily appreciate; I certainly didn't. Chapter 4 opens with the importance of gesturing, an action we take for granted and therefore, often fail to notice when gesturing does not occur. For example, I remember at a general parent support meeting, one of the parents talked about how her son was taught to nod his head, "yes" or shake his head, "no." She never noticed that her son did not nod or shake his head along with the verbal communication, until she learned to notice. Gesturing is a major component of our social communication, from the most visible (pointing, turning of our bodies) to the subtle (the way we raise our eyebrows, whether we turn our body at a certain angle, even the way we smile with our eyes or with only our teeth) - these hold clues to the totality of human communication that our children on the spectrum may not infer and need explicit instruction.

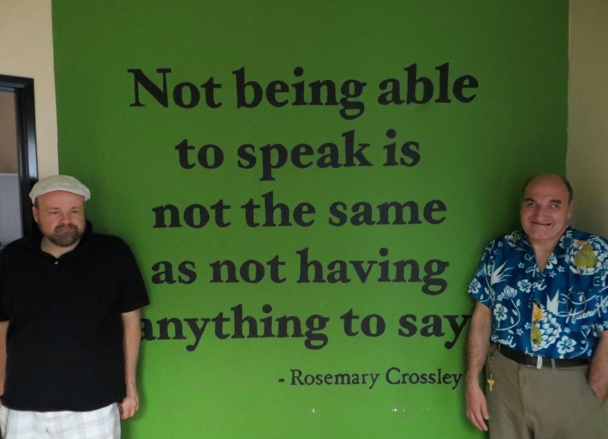

To me, mastering the totality of communication allows a person to start "predicting" and "anticipating" a social interaction with another person, which then helps lessen anxiety and fear that comes from lack of predictability from one's environment. I personally believe that our children can learn these rules, just as "typical" children have learned these rules, only that our children have to learn these rules in specific steps and through explicit instruction... but our children can learn these rules. I know that parents are eager to hear their children's voices: I was there! But now I appreciate more and more the importance of hearing my child's "nonverbal communication" in the form of pointing and gesturing, because these forms of communication are as critical to my child's ability to navigating social exchanges as verbal communication. I was glad to see Dr. Paparella include this early on in the topic that is a major draw for parents like me.

For newly-diagnosed parents, you are learning aspects of basic behavioral instruction even when you may not realize that you are. Terms like "errorless learning" and "prompting" and "prompt hierarchy" will become every day terms for you down the road, but you're learning what these terms mean so that you can become informed when you hear them again when evaluating the behavioral approaches that may work best for your child's instruction.

Chapter 4 discusses eye contact, which honestly I didn't care much about at the beginning. I was one of those parents who couldn't believe my child was on the spectrum because he had eye contact. However, over time and after gaining some "experience" along this journey and also shedding my blinders, I began to see that my child's eye contact was inconsistent. Since we live in a society where eye contact is often the first line of communication and an important non-verbal communication, we parents have to require eye contact.

And yes, all of this seems overwhelming at the beginning. I remember being told by another mom that soon this will all be second nature to me, and I didn't believe it. Yet now I routinely gauge the complexity of my language, checking to see whether I may be inadvertently reinforcing my child's echolalia by "echoing him" (therefore teaching him by example), and sometimes as soon as a sentence leaves my tongue I knew that sentence was too vague or had too many complicated parts. All this happens within a blink of an eye. That's when I realized: this has indeed become second nature to me, and honestly, become easier over time. You can learn this, and this will become second nature to you.

Chapter 5 gives good ground rules for building social engagement with our children, and enthusiasm (yours) is the major component. For those of you who are hemming and hawing about exaggerating your enthusiasm, let me just say this: it doesn't matter how you feel about exaggerating enthusiasm ("oh I can never be that silly!" or "that's so fake!" or "I'll feel so weird doing it!") you can silently think all these nagging thoughts in your head but as long as you DO IT you get to keep all these judgments if you want to keep them. In this arena, it matters what you do even if what you think and how you feel aren't always congruent. DO. [I've suffered from major clinical depression, I'm an introvert, and I'm full of self-criticism (I forgot to mention, I'm also Asian, I come from a culture of self-restraint and emotional containment) so I have more excuses than most to explain why I'm incapable of exaggerating my enthusiasm. Yet I have learned to throw a "praise party" when my child makes effort, because practice makes perfect and I'm committed to practicing as best as I can.]

Chapters 6 (Sharing Experiences) and 7 (Imitation) gives parents an instruction for modeling social interaction that have been shown by research to facilitate language acquisition. These chapters contain the mechanics of "how" to create the situations ripe for sharing experiences or to encourage children on the spectrum to imitate. These chapters also continue to introduce terms like discrete trial training (DTT) and generalization, which you will use as part of your daily vernacular, in time. Again, these chapters hone for me the importance of "non-verbal" aspects of communication, and how these non-verbal aspects build toward a verbal communication in our children. These also become important for our children to begin learning from their environment in greater capacity than before they were taught "how" to join attention and imitate.

What has been tough for parents like me is that I didn't know I had to "systematize" these processes until now. I'm no longer a parent who can take for granted my child's ability to join my attention, share my experience, or imitate as a matter of fact. Therefore, I am required to break down these processes that "other" parents don't have to think twice about, and then I have to learn how to teach these processes to my child. For some of us, these processes may not feel natural and we feel somewhat contrived and strange teaching it... my way of saying "it's normal to feel like you don't know what you're doing, as long as you keep practicing and it becomes almost second nature."

Chapter 8 (Change Unusual Behaviors) is one I know many parents will pay close attention to. This is because our children's "unusual" behaviors - "stimming" in autism parlance are often the most visible signs of our children's differences even before they open their mouths to speak (then we have the auditory signs of our children's differences, whether or not they speak and what they speak about and how they speak.) This chapter guides parents through the possible functions of the behavior for the child and more importantly, suggests possible "socially acceptable" replacements. Most of us probably know how hard it is to break a habit, especially habits that are self-reinforcing: we stand a better chance if we have a replacement habit that gives us a matching level of reinforcement.

"Flexibility is Key" is a Chapter 8 topic that I think needs its own chapter, because I wanted to read more than 3 pages of this critical "life skill." Flexibility is another aspect that many parents take for granted, but parents like me cannot... and yet flexibility (or adaptability as I tend to think about it) seems to me a critical "survival" skill. Maybe in our developed society, this has more to do with social survival than physical survival, but flexibility is critical to survival nonetheless. [Dr. Paparella, if/when you write a second edition, I'd love to see an entire chapter devoted to Flexibility/Adaptability.]

Entire discussions can grow from this chapter about unusual behaviors, because it is a "hot button" between those from the autistic community who may view "stimming" one way (part and parcel of the autistic presentation warranting total acceptance), while parents of autistic children may view stimming very differently (what causes their kids to be ostracized and bullied.) I know of parents who cannot tolerate any amount of "stimming" no matter what kind of stimming this is. I know of parents who cannot even say the word "stimming." I've come to view parental perspectives toward stimming as a divisive factor in the "autism parenting" group.

I belong to the group that allows "stimming" based on situations with my child. At the end of the day when my child is tired, I turn a blind eye to his "stimming" whether this is lining things up or turning everything into a vacuum cleaner. The kid needs a break. If he is anxious, I know he will probably script (delayed echolalia). If I cannot offer him a better alternative or redirection or coping skill, I do not interfere. This doesn't mean I don't feel that tightening knot in my chest, knowing how others who don't understand may look at him with curiosity. This doesn't mean I don't feel that overwhelming temptation to tell him to stop, just stop. This doesn't mean I'm not already projecting forward and wondering if what I'm doing is somehow setting my kid up to be a future bully-target. I feel - and fear - all these things but I don't let my own anxiety of judgment (toward my child or toward me as a mother) interfere with my child's way of coping with his anxiety... because I can't yet give him a different or better way.

I wish all "newly diagnosed" parents read Chapter 9. It will save parents a lot of money and emotional roller coaster of riding the autism biomedical treatment industry. Dr. Paparella is diplomatic and understands why parents jump on bandwagons. Her position is, "...to always support parents as long as there is no potential harm to the child." The reality is that many parents will not consult with their child's psychologists about these biomedical therapies, preferring to listen to anecdotes of peer parents. The reality is that parents' desperation for hope and signs of "improvement" in their children can and do color parents' perception of what is "potential harm" to the child. The power of a peer testimonial cannot be underestimated. I have been in the same room with parents who are so enthusiastic about a particular "therapy" that other parents immediately go buy whatever their peers have bought for their children, hanging on the hope that their child will "be cured".

Dr. Paparella touches upon pharmacological approaches in 2 paragraphs without naming specifics, which is sufficient for the scope of this book. The chapter discusses educational and behavioral intervention and is a good introduction to behavioral treatment approaches. I remember asking Dr. Paparella a question about different behavioral approaches and she described the spectrum of interventions from Floortime to DTT. I liked looking at these behavioral interventions as a "spectrum" because it aligns with our children are on a "spectrum" and it is more about finding the matching approach to our individual children.

In the section "What We Know" Dr. Paparella uses National Research Council's guidelines on interventions for children on the autism spectrum. She gives a list of 10 items that parents can follow to gauge the "what, how, and how much" around their children's early intervention. She also gives parents guidance of when things need to change for example, if a child does not make progress in 2 weeks with a 5 day a week program. This gives permission to new parents, who are often anxious and doubtful about their lack of "expertise" when weighing their observations against "expert opinions" to change programming because their children are not responding.

I had to laugh at NRC's "intensive" intervention of 25 hours/week. I laugh because the level of "intensity" I am bombarded with as a parent is 40 hours per week (minimum)! I know parents who think 50-60 hours per week is very reasonable and absolutely defensible. Special education attorneys routinely fight for weekly 40 hour ABA program funding from the school district, citing the 1987 Lovaas paper as research-based proof for wanting these hours. The definition of "intensity" in autism intervention seems to have shifted from when NRC published its guidelines in 2001. Now it seems like a parents' race to cram as much therapy into every conceivable hours of a child's day, in order to be considered a "good parents, doing everything they can," for their autistic child, regardless of how impacted their children are. The knife cuts both ways: if your child is higher functioning, then you should do everything you can to "make her look normal"; if your child is lower functioning, then you should do everything you can to "improve his functioning." There is so much pressure on the parents when it comes from speaking with other parents. We don't even need to overtly pressure each other: it only takes one enthusiastic parent to evangelize to other parents a therapy or way of thinking...

In Dr. Paparella's closing thoughts, she included a note that said, "I hope it brings you many hours of practical and exciting instruction, and joyful times with your child." I think the reason why this book is so important - why this book is so needed why this book is so critical at this moment in time for our children on the spectrum is that many of us parents have forgotten what joy feels like. Some of us have forgotten what our relationship with our children feels like. Maybe some of us have forgotten that our children even feel. Some of us have stopped looking at our time with our children as "joyful". Some of us have bought into the hype and the fear and peer pressure, thinking if we don't "hit 'em with everything we got," we must not love our children as much as other parents who are "throwing everything but the kitchen sink" at their children.

Thank you. Dr. Paparella for seeing our children as they are, holding the highest regard for each of them, and for helping parents like me navigate this emotional journey with my eyes and heart wide open for my little one.